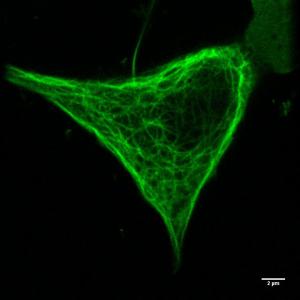

Microtubules – the transportation network of the cell. The darker area in the upper left is the cell’s nucleus.

Rarely is an image both beautiful and scientifically valuable. This image wouldn’t win any awards, but it’s what I see day in and day out. An ordinary cell with ordinary structure, destined to sit forever on a dusty hard drive with tens, if not hundreds, of similar images.

The Wellcome Awards showcases images that are not only visually stunning but also scientifically interesting and technically challenging.

This year’s crop of 16 celebrated images includes a view of a live human brain (not for the faint of heart), up close and personal with a lavender leaf and an image of crystallized caffeine. You can see all the winners in a slide show from the Wellcome Awards link in the second paragraph.

Today’s Google doodle celebrates the 144th anniversary of Polish-born physicist Marie Curie’s birth. Madame Curie was a remarkable woman and scientist celebrated the world over for her massive achievements in scientific research and professional advancement. Born Marie Sklodowska in Warsaw, Poland on November 7, 1867 she was the youngest of five children born to a secondary school teacher and his wife. At the age of 24 she moved to Paris, France to study at the Sorbonne, where she earned degrees in Physics and Mathematics. During her studies she met and married and Pierre Curie, a professor in the Sorbonne’s Department of Physics. The Curie’s early work pioneering the study of naturally occurring radioactive elements earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903. Once she earned her Doctorate in Science (also in 1903), Mme. Curie took over her husband’s position as head of the Physics Laboratory at the Sorbonne and upon M. Curie’s death in 1906 she took over his position as Professor of General Physics, the first woman to hold such a position at the Sorbonne. In 1911 the Nobel Committee again recognized Mme. Curie’s work in radioactivity, including her work on the discovery and characterization of radium and polonium, and awarded her a second, unshared Nobel in Chemistry, making her the first person to be awarded a Nobel in two different fields*. In 1914 she was appointed Director of the Curie Laboratory in the Radium Institute at the University of Paris, where she continued her work in radioactivity. Tragically, Mme. Curie’s work caused extensive exposure to radioactive elements before the dangers of these elements were fully understood. She developed aplastic anemia and died in southeastern France in 1934, aged 66.

* Marie and Pierre Curie are also the parents of a Nobel Winner. Their daughter Irene Joliot-Curie shared the 1935 Nobel in Chemistry with her husband, Frederic Joliot for their work on the synthesis of artificial (man-made) radioactive elements.

No correct guesses for this week’s Whatsit, apparently no one looks as hard at their herb garden as I do. This is the tip of a leaf of basil, which I have moved indoors now that it’s getting rather cold at night in the upper Midwest. Its one of the last touches of green in an increasingly brown world. April did put in a good guess of evergreen needle, but since that one’s sort of been done in Whatsit form already I thought I would mix it up a little bit.

No correct guesses for this week’s Whatsit, apparently no one looks as hard at their herb garden as I do. This is the tip of a leaf of basil, which I have moved indoors now that it’s getting rather cold at night in the upper Midwest. Its one of the last touches of green in an increasingly brown world. April did put in a good guess of evergreen needle, but since that one’s sort of been done in Whatsit form already I thought I would mix it up a little bit.

Hopefully I can add a picture of the whole basil plant and a little information on this wonderful herb later today or tomorrow, but I wanted to get the answer out at its usual time.

Here’s this week’s Friday Whatsit, a touch of green in an otherwise very autumn-tinged Midwestern world.

Here’s this week’s Friday Whatsit, a touch of green in an otherwise very autumn-tinged Midwestern world.

What is this thing, with its jagged edges and many pores? Bonus points for something more specific than the general category, you’re a smart bunch.

Guesses in the comments section, answer will be posted on Monday!

From the wonderful world of Facebook, my sister has uploaded a link to an American Geophysical Union blogosphere post with the best Halloween costume EVER*. It’s a man dressed as frog spawn. I kid you not.

Biology, bubble wrap, it’s a total nerd-stravaganza. Bubble-wrappy hats off to you sir, that is awesome.

* Or at the best I’ve seen this year. Tiny Science is big on hyperbole.

The winners of the fourth annual “Dance Your PhD” contest have been announced! From 55 entries submitted by graduate students worldwide, four winners were chosen (one each in Physics, Chemistry, Biology and Social Sciences). Physics category winner Joel Miller of Western Australia University also took the Grand Prize for his innovative stop-action film “Microstructure-Property Relationships in Ti2448 Components Produced by Selective Laser Melting: A Love Story.” Sounds awesome, right? Each of the four category winners received $500, and the Grand Prize winner received $1000 and a trip to the upcomming TedxBrussels conference*. You can view all of the winning videos at BioTechniques and read about last year’s contest here.

*Tiny Science LOVES Ted. You should too!

A number of our guessers went for the pickled foodstuff angle, which is on the right track. Although I have to say I’ve only seen two pickled foods that are red: pickled cucumbers soaked in red Kool-Aid and pickled beets. And these, dear reader, are pickled beets. Thanks to lovely neighbor Gina for correctly guessing their identity as Beta vulgaris, and also for bringing them over to our house in the first place.

There are five main varietals or subvarietals of beets: the common garden beet or beetroot plant which is grown for its red roots (like these here); the spinach beet and (Swiss) chard, both grown for their large, edible leaves; the mangelwurzel, a tough, fibrous beet grown as a feed crop for animals; and the sugar beet, developed in 19th century Germany as an alternative to sugar cane. All these varieties are descended from the Sea Beet that grows wild on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

Humans have been eating beets for thousands of years, first discovering the tasty leaves, and then developing the root and sugar varieties. The world seems to be divided into two camps on beets: love them or hate them. I personally love them, especially pickled. I blame my Northern European heritage for my love of both cheese and all things pickled. Pickling and cheesemaking are two ways to preserve food through long winters. We forget in our world of refrigeration and global food distribution that for much of human history we grew, hunted or gathered our food, and if you lived in a place with cold winters some food had to be stored for months. Pickling as a process is a close cousin to fermentation. It involves soaking food in a brine solution, which allows certain types of food-friendly bacteria to thrive while keeping others out.

Pickling also adds a lot of salt to the food in question, leading some to discover the joys of electric pickles. There are two kinds, the kind where a pickle connected to a battery will glow (and possibly get really, really hot and catch fire, so be careful with this one kids) and the kind where the pickle itself can be used as a battery to light a light bulb. Other foods often used as batteries include potatoes and lemons. You won’t be able to go green and run your house with them, but done carefully (we are talking about an electric current, nasty zaps are possible) you can have some science fun with your food.

Many of you have been on pins and needles waiting for the Friday Whatsit to come back. Well, here it is!  October is the month for creepy-crawly spooky stuff, and this jar of whatsit items reminded me of elementary school Halloween parties and all the faux-creepy stuff people would put out as decoration. You know, bowls of spaghetti “brains” and peeled grape “eyeballs.” Don’t remember that kind of stuff from your childhood? maybe I just grew up in a weird part of the world.

October is the month for creepy-crawly spooky stuff, and this jar of whatsit items reminded me of elementary school Halloween parties and all the faux-creepy stuff people would put out as decoration. You know, bowls of spaghetti “brains” and peeled grape “eyeballs.” Don’t remember that kind of stuff from your childhood? maybe I just grew up in a weird part of the world.

Anyway, what are these globular things in this big jar of reddish liquid? Leave your guesses in the comments section and I’ll post the answer on Monday.

. . . and so is Tiny Science! I know! Try to contain yourselves, please.

So, if you are not a big reader of this blog, you may be asking yourself, what is Month at the Museum? It’s the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry’s month-long experiment in which one lucky person gets to live and work in the museum 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. This year’s M@TM contest winner, Kevin Byrne, will be eating, sleeping, blogging and tweeting his way through the museum from October 19th – November 17th. Kevin has some cute shoes to fill. Last year’s M@TM participant, Kate McGroarty, had a fabulous time and shared her enthusiasm with the world through her blog, Twitter feed and — my personal favorite — Snuggy Science videos. So if you haven’t yet, check those out and whet your appetite for Month at the Museum 2.

Continuing my comments on the Boing Boing article on scientific peer review by Maggie Koerth-Baker. As I said before, I only slapped myself in the head a couple of times while reading this article, so I consider it pretty good. Once we got past the difficulties in describing accurately what a journal article is and is supposed to do, the description of what goes on during the peer review process was (scarily) accurate.

Part Two, in which we talk about the behind-the-scenes aspect of peer review: who are peer reviewers and what really goes on during the peer review process?

When an article is submitted to a peer-reviewed journal, the editor chooses two or three people in the field and sends them the article to read and comment on. As I said in Part One, the reviewers can comment on any part of the work, from the initial hypothesis to the inclusion of references. The only guideline is usually that the article fit the quality standards and theme of the journal. These are admittedly very vague criteria.

The theme of the journal is usually pretty obvious; no one submits an article on cells of the immune system to a journal called “Neuroscience” unless it contains information they think will be important to people who study the brain and nervous system. But for journals like Cell, Science and Nature, the criteria for fitting the theme are more vague, and usually go to “high impact” (read from a large, well known lab unless your idea could change the world and then maybe we’ll let you in) papers.

If the theme of a journal is vague, the quality standards necessary for publication are even more so. These standards are largely unwritten and, as Ms. Koerth-Baker points out, left to the individual reviewing the paper to determine.

“For the most part, scientists are not formally trained in how to do peer review, nor given continuing education in how to do it better. And they usually don’t get direct feedback from the journals or other scientists about the quality of their peer reviewing.“

This is true, for the most part. Unless a student’s advisor gives them articles to review and then checks over their work to provide feedback, there are few ways to learn how to critique an article and little feedback on how relevant or helpful the comments are. Since advisors have very little time to even review papers, let alone get someone else to help them and guide their progress, this only happens if a student is very lucky and has an advisor dedicated to the well-rounded training of students.

There is one formal mechanism where young scientists are given training and feedback in peer review, at least where I was trained: journal clubs. Journal club is like a book club.* One member of the group picks an article that they think will interest the group. Then everyone reads it, and the person who chose the article presents a summary of the article and their thoughts on the quality of the work. Graduate programs often have journal clubs for their students. Everyone thinks they are a big pain in the you-know-what because they take up a lot of time that we (and our advisors) feel that we should be spending doing research. But they can be valuable tools not only for learning about new articles that come out in a field, but for learning how to read and critique a report on a scientific study.

“If a paper is peer reviewed does that mean it’s correct? In a word: Nope. Papers that have been peer reviewed turn out to be wrong all the time. That’s the norm. Why? Frankly, peer reviewers are human.”

Um, frankly, scientists are human. If the ideas in a paper turn out to not be “correct” it could be that the peer reviewers didn’t do a very good job. Articles that are a load of crap get published all the time. Usually the lesser known the journal, the more likely this is to happen.

But even well reviewed papers in good journals have ideas that look correct at first, and then turn out in the end to be not really the way things work. That’s just how science is. Ideas get published, then people in other labs look at those ideas and think about ways that they can refine and extend them. Sometimes in refining and extending them, they find out that the idea in the original paper wasn’t exactly correct. Or that there were aspects of the idea that the first group didn’t see or didn’t get around to addressing. This is why, like we said in Part One, it is very rare that one journal article is the definitive word on any scientific idea.

“You should think critically and skeptically about any paper—peer reviewed or otherwise.”

Yes, so true. Whenever I read anything someone has written, my critical thinking cap is always on. The main question to keep in mind whenever you read a piece of scientific research is “does this make sense in the context of the field?” Context is very important whenever scientific ideas are discussed, which is why every paper begins with a discussion of the field in general and the context in which the new ideas presented should be placed. If the data in the paper can connect to other ideas published by other groups, this makes the whole field stronger. If the data in the paper are refuting other people’s ideas, or appear to be in conflict, the authors should carefully explain why they think that others’ ideas may not be entirely correct, or why their ideas are different but still fit into the overall framework of the field.

This brings up a related point that some science journalists miss, which is that in order to adequately review a paper you must first know the field, and if you are taking your review to a wider audience, you must first explain the field. The right context for scientific ideas is not always the same as an individual’s worldview, but when the current knowledge is not explained properly, that’s often the only context a reader has.

” Scientists are frustrated that most journals don’t like to publish research that is solid, but not ground-breaking.”

This is true. If you are the first person to come out with something truly novel, you may get published, if your lab is headed by a big name researcher, or you may not, if your lab is more obscure. If you are somewhere near the beginning, after the idea has been accepted, you’ll very likely get published. But if you are following up on an idea that has been “done,” especially if it’s to publish more evidence that it is right, you will have a hard time finding a journal for your ideas. Which is odd, considering what we just talked about in the previous paragraph, which is that context is critical and that connecting to and being supported by other ideas in the field is an important thing for a new publication to achieve.

Ironically, the opposite is true when it comes to funding. Scientists are also frustrated that government agencies like the National Institutes of Health seem to want to fund research that is more of the same solid stuff that has been done before and will work again, even though they say they want to fund research that is risky: potentially ground-breaking but potentially a spectacular failure. But that’s a story for a different day.

“They’re frustrated that most journals don’t like to publish studies where the scientist’s hypothesis turned out to be wrong.”

Ah yes, “The Journal of Stuff that Didn’t Work.” How we would love to have that journal. It would be the largest, most widely read journal in all of science, right next to “The Journal of Lovely Preliminary Data for Ideas Ultimately Too Hard to Complete.” Why? Time for research is limited, so if someone else already tried a series of experiments and it didn’t work out, it would be nice to know so as not to waste time going down the same path.

From the comments section:

“I expect the cost for most modern scientific experiments to be rather exorbitant — time, materials, equipment, staffing etc. I also understand that existing research is based on findings of earlier research, but in that case, how many scientists will first go back and verify the original findings, before going forward with their own research?”

All the time. We have to. Repeating a couple of experiments from someone else’s publication is a good way for a lab to figure out if the system they have set up in their lab matches the system another lab used to create their data. If the two systems are similar, it will be easier to fit the ideas from both labs into the same context and advance the field. However, these repeats are rarely published, because journals are often only looking for the new and novel, not independent confirmation of exactly the same experiments. This is why labs often create elaborate new systems in which to test their ideas, instead of building on others. It increases the novelty of their work, but also the difficulty in comparing it to and linking it with other work in the field.

——————-Footnotes———————————

*I know this is an odd thing to say when in Part One I ragged on the author of the original article for likening journal articles to book reports, but, such is life.